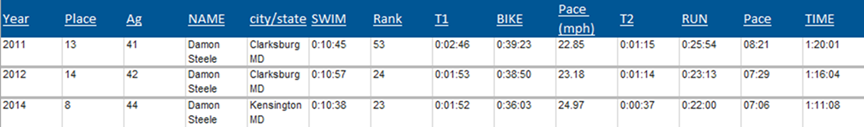

A longtime athlete of mine recently sent me some race stats from a sprint triathlon he’s done three times now. You can see the data in the chart below. It shows his splits from those three years from 2011 to 2014; the most recent race was just a few weeks ago. That chart inspired this post, as there are multiple awesome conclusions I draw from this data that all lead to one big message:

It takes time to get fit and reach your potential as an athlete. Hiring a coach is the best way to get there, but you can’t expect that coach to magically make you fit overnight or even a few months.

(As an aside: I don’t even think Damon has reached his potential as sprint triathlon, as usually it’s a lower-priority goal compared with the bigger races he’s done, but even with that being the case we see him getting fitter at the distance every year namely the run.)

~~~

I often see athletes having rather unrealistic expectations about their fitness progression. They want immediate results. They want it now. It’s no surprise that’s the case; this day in age we live in a society in which immediacy is the norm and valued very highly. People want fast results. Whether fast food to take on the go (which, not surprisingly, is terrible for you and poor quality) or a crash diet for fast weight loss (which, again, is terrible for you and likely leads to gaining that weight back — and some — down the line), these expectations for fast results aren’t realistic for longterm success, and in many cases they’re not healthy, either. They may work in the moment, but you’re cutting yourself short if you always go this route.

Especially when it comes to endurance training. We can’t “cheat” basic physiology. I think it honestly takes at least three dedicated seasons to start reaching your potential in endurance sport — triathlon especially when you’re juggling training for three sports. This includes developing a solid endurance base, building resilience to injury, developing metabolic efficiency and honing in on race-specific skills. Granted, there are exceptions for the rare abnormally gifted athlete who becomes an overnight phenomenon (genetics!), but for most of us to really get fit in triathlon it’s a longterm commitment of at least three years. And I say that as both a longtime triathlete and coach. I would assume other coaches agree on some level — they may even say it takes longer.

So then let’s talk about the athlete’s mindset in hiring a coach, and why this matters. There are generally two situations.

1) Many athletes hire a coach for a race they’ve already signed up for and it’s taking place within a year or less. They have an epiphany that they need help to figure the best training in their already-busy schedule in order to have the best possible day, and they need a coach to crack that code. That’s fair and a valid reason to hire a coach. We coaches take out the guessing game and just give you the assignments. In my experience coaching, most athletes come to me anywhere from 3-12 months before their “A” race. During the free consult I have with potential clients, I often get asked, “Is it too early to start training for X race?” Never once have I said yes. It is never to early to start the road to fitness and developing the coach-athlete relationship. More time to prepare is always going to be better. Even if that means 6 months of General Prep — aka setting the foundation and “training to train.”

Give your coach time to develop your fitness and help you reach your potential. It may take years to do so.

2) On the flip side other athletes hire a coach for longterm development and/or hire a coach potentially several years before their big “A” race (aka, for example, they hire a coach saying they hope to qualify for Kona in 3-4 years knowing that fitness development takes time). I would say this is not as common as that first scenario; although, I wish this “longterm outlook” was more the norm. It’s a coach’s dream come true when an athlete is looking at the big picture and wants to take the time (years) to develop fitness — no rush, lots of flexibility, and plenty of opportunity to get that athlete to his/her potential. You can race as little or as much as you want on the road to that eventual A race, too.

Getting back to that chart above. You can see how it took years for Damon to really start nailing his bike and run (side note: he came to me already a phenomenal swimmer so at his level you won’t see drastic improvements on swim times but 1) he has become more efficient which helps bike/run and 2) you can see in his rankings on his swim here that he’s gotten stronger relative to the field and stays consistent even when water conditions vary as they did in this race). Speaking to his bike/run combo, had I tried to get him “fit” for that kind of extreme improvement in speed within just a few months of starting together we may have not had the same results, and worse: we could have risked breakdown and injury by doing too much too fast with too big of expectations. Going from an 8:21 avg off the bike to a 7:06 avg off the bike is a great improvement but not one that can be achieved in merely a few weeks. Especially for amateur athletes in which training is usually a lower priority on the list compared with work and family. That run improvement is also a testament to Damon’s bike and how we’ve dialed that in; using a power meter has helped tremendously.

So that said, what happens when an athlete does come to me 3 months before an A race? (It happens!) In those cases, I’m ready and motivated to do all I can to help, but I won’t lie, it’s a tough scenario and requires a lot of careful attention from me. It’s absolutely possible to benefit from a coach even in that short time; however, the athlete cannot expect the “overnight results” of going from one extreme to another. So, in those cases I tell the athlete that we can get it done and get him/her to the start line, but to consider choosing another race further out for which we can spend the time to really develop athletic potential. Not to mention, if you’re looking at 3 months from hiring a coach until race day there are other factors to consider like developing the relationship. I don’t give cookie-cutter programs, and it takes me at least several weeks or more just to figure out how the athlete responds to training and what he/she really needs for success. (I give an very extensive questionnaire upon commencing our training, which is quite helpful but then we need to put it into practice). Each person is different and I need to tweak the variables to find the right formula. This takes time.

From an athlete’s perspective, it can get frustrating if you aren’t seeing results right away, though, especially if you’re paying the money. I get it. So what should you do? First off, don’t jump to conclusions and blame it on your coach. Your coach may be doing the right thing and it just takes time to develop your fitness! Talk with your coach and communicate — perhaps there’s a plan the coach isn’t verbalizing clearly but once he/she does it makes sense and the athlete then understands that some patience is needed before the results start coming (MAF training is a good example here). That said, there are those cases where coaching is like dating and you may have to cycle through a few coaches before finding your right match. But to that I say 1) choose wisely, 2) once you choose give the relationship and program time, and 3) be open-minded to the coach’s plan it’s why you hired him or her — let him do the job for which you’re paying.

Bottom line?

Getting fit and reaching your potential as an endurance athlete takes time. If you’re looking to hire a coach please consider making it a longterm investment with that person and not just a “one-and-done” so that your coach has the opportunity to truly develop your skills. I know finances may factor in here, and many folks can’t afford year-round coaching for multiple years. In those cases you can at least hire a coach short-term to learn some tricks of the trade then part ways with a new knowledge base and do what you need to do on your own. However, if you can afford the longterm coaching route, give your coach the time and always remember that the coach-athlete relationship must be fostered with constant communication over long periods for the maximum success in the athlete’s racing.

Either way — “one-and-done” coaching or longterm coaching — just know that you have an underlying potential that may take years to bring to fruition. Being your best takes time and there are no shortcuts, otherwise you’re cutting yourself short of reaching potential.